The Gap Between Governance and Lived Experience

There is a growing tendency in the housing sector to discuss performance through a single lens at a time. Tenant satisfaction surveys are cited in isolation. Ombudsman findings are treated as exceptions. Regulatory grades are presented as proof of organisational health. What happens far less often is that these measures are placed side by side.

When they are, a clear and uncomfortable picture emerges.

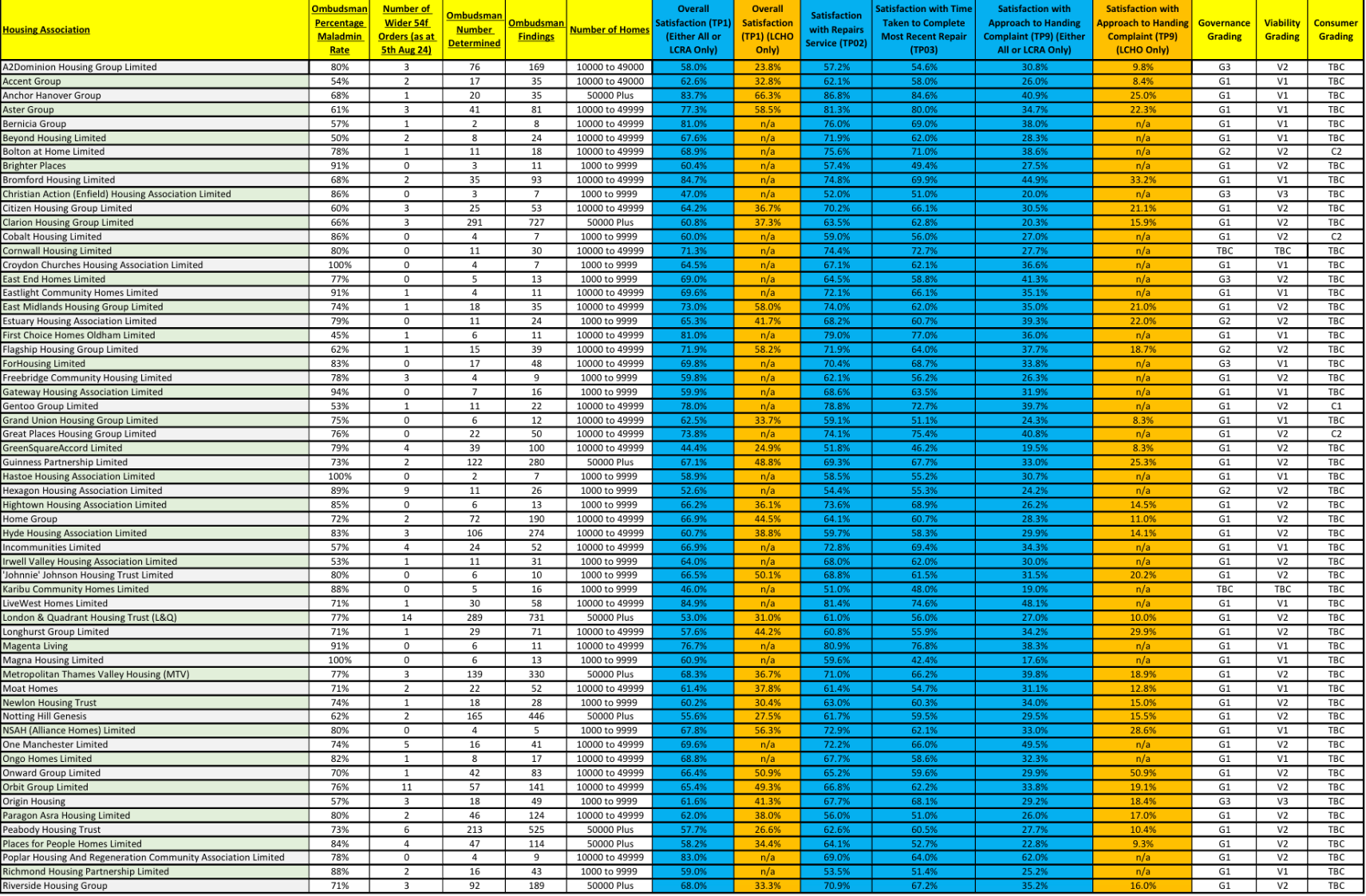

Data discussed recently on the Housing Sector Podcast brings together three sources that are usually kept separate: Tenant Satisfaction Measures, Housing Ombudsman outcomes, and Regulator of Social Housing governance and viability grades. Looked at collectively, they expose a widening gap between how housing providers are assessed on paper and how residents experience housing in practice.

This is not about one landlord. The same pattern appears repeatedly across the sector.

Satisfaction scores do not prevent failure

At first glance, Tenant Satisfaction Measures appear reassuring. Many providers record overall satisfaction scores in the 60–80 per cent range. Repairs satisfaction is often higher still. These figures are frequently used in annual reports and board papers to demonstrate progress and stability.

But when these same providers are examined through Ombudsman outcomes, the picture changes.

High satisfaction scores do not correlate with low maladministration. Providers with strong headline satisfaction figures still attract significant numbers of upheld complaints, formal findings, and orders for redress. The data suggests that satisfaction surveys are a blunt tool. They capture sentiment at a moment in time, not systemic problems, and they do not reflect what happens when things go wrong and residents try to challenge decisions.

Source - Ebrahim Goolamall https://housingservicechargeandrentpiperdy.com/

Complaint handling is the fault line

Across the dataset, one metric consistently stands out: satisfaction with complaint handling.

While overall satisfaction may sit comfortably above 60 per cent, satisfaction with complaint handling frequently drops into the teens or low twenties. In some cases, it falls into single digits.

This matters because complaint handling is not a peripheral issue. It is the mechanism through which disrepair, safety concerns, service charge disputes and administrative errors are resolved. When complaint handling fails, issues escalate. When issues escalate, residents turn to the Ombudsman. When that happens, maladministration findings rise.

The data shows this chain clearly. Poor complaint handling satisfaction aligns closely with higher volumes of Ombudsman findings. This is not coincidence. It is cause and effect.

Governance ratings remain strong

Perhaps the most striking feature of the dataset is what happens when governance and viability grades are introduced.

Many providers with weak complaint handling satisfaction and significant Ombudsman findings retain strong governance ratings, often at the highest level. Viability grades also remain stable. From a regulatory perspective, these organisations are judged to be well run.

This raises a fundamental question: what is governance measuring?

If governance frameworks allow repeated failures in complaint handling, sustained maladministration findings, and low resident confidence to coexist with positive ratings, then governance is not capturing lived experience. It may be measuring financial controls, board structures, and reporting processes, but it is not measuring outcomes for residents.

Scale does not explain the gap

It is tempting to attribute these issues to scale. Larger landlords will naturally generate more complaints. But the data suggests this explanation is insufficient.

While large providers do attract higher volumes of cases, the weakness in complaint handling satisfaction appears across organisations of different sizes. Scale may amplify the problem, but it does not cause it. The underlying issue is process, culture, and prioritisation.

Residents experience this not as a statistical trend but as delay, defensiveness, and exhaustion. For many, the complaints process becomes something to endure rather than a route to resolution.

What this means for residents

From a resident perspective, the gap between governance and lived experience is not abstract. It is felt when emails go unanswered, when complaints are closed without resolution, when escalation is treated as hostility, and when the only remaining option is an external body.

The data shows that these experiences are not isolated. They are systemic.

Residents are being told, implicitly, that their dissatisfaction does not register as organisational failure so long as governance metrics remain intact. That message erodes trust, not only in individual landlords but in the regulatory framework itself.

Why joined-up data matters

The most important lesson from this dataset is not that one metric is wrong, but that no single metric is sufficient.

Tenant satisfaction measures, Ombudsman outcomes, and regulatory grades all serve a purpose. But when they are viewed in isolation, they allow contradictions to persist. Only when they are examined together does the gap become visible.

If the housing sector wants to rebuild trust, it must stop assessing itself in silos. Governance must be connected to outcomes. Complaint handling must be treated as a core service, not an administrative function. And lived experience must be recognised as a valid measure of performance, not an inconvenient one.

The data is already there. The question is whether the sector is willing to look at it honestly.

I want to thank my friend Ebrahim for his diligence and his tireless support of both this work and the wider housing sector, as well as his unwavering willingness to speak out on corruption, safety, Grenfell, and Awaab, and why these issues must continue to be raised with evidence and integrity.

Stay strong Ebs.

https://housingservicechargeandrentpiperdy.com/

https://www.linkedin.com/in/ebrahimpi/