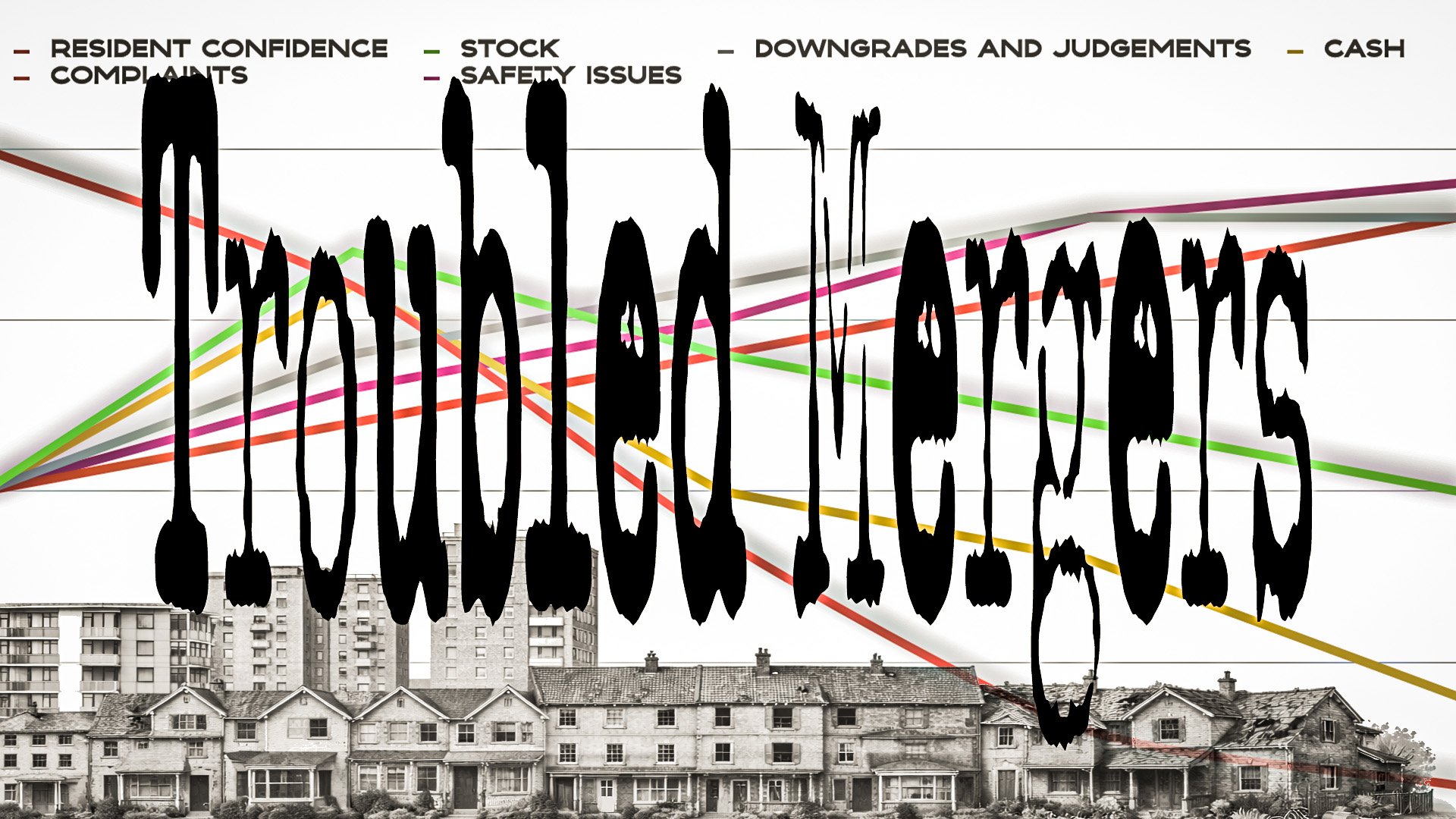

Troubled Mergers & Why They Should Trouble Us All

Introduction

This is not a personality piece. It is a record of decisions, outcomes, and accountability — or, more accurately, the absence of it. It is a clear account of the ongoing failures of GreenSquareAccord under the leadership of Ruth Cooke.

Ruth Cooke was brought in to oversee the merger that created GreenSquareAccord in April 2021 and to lead the newly formed organisation. The outcomes of that merger — including its failures, shortfalls, and consequences — sit with the leadership responsible for delivering it.

The record that follows covers her tenure as Chief Executive and asks a simple question: how long will she be allowed to fail, and how can anyone continue to place trust in leadership when failures are now so frequent and ongoing that judgement must surely be made?

Pre-Merger: GreenSquare’s Own Compliance Failures

Before the GreenSquare–Accord merger was proposed, GreenSquare Group was already under regulatory scrutiny for serious compliance failures. This context matters, because it undermines later attempts to frame post-merger problems as issues inherited solely from Accord stock.

In March 2019, the Regulator of Social Housing issued a regulatory notice to GreenSquare Group after concluding that it had breached the Home Standard. The notice related to failures in meeting landlord health and safety obligations, including shortcomings in fire safety management and the implementation of actions arising from fire risk assessments. Reporting at the time also linked the intervention to the discovery of overdue gas safety certificates and issues relating to lift safety.

The seriousness of these failures was reflected in the Regulator’s response. GreenSquare was required to commission a root-cause analysis that went beyond operational processes and examined governance, leadership, and organisational culture. This was not treated as a technical lapse, but as a systemic failure requiring senior-level scrutiny.

GreenSquare acknowledged that 2018/19 had been a “challenging year” and made changes at executive and board level following the regulatory judgement. These events occurred before any merger with Accord was completed and before the formation of GreenSquareAccord.

Following the regulatory findings, GreenSquare replaced its chief executive, Howard Toplis, with Ruth Cooke in February 2019. Mr Toplis did not leave the sector. In April 2020, sector publication Inside Housing reported that he had been appointed chief executive of Tai Calon Community Housing.

The article explicitly noted that Mr Toplis had previously been replaced at GreenSquare after the landlord was found to have breached regulatory standards on fire, gas, and lift safety. Rather than being treated as a terminal leadership failure, the episode was presented as a managed transition. The regulatory breaches that occurred under his tenure did not prevent his reappointment elsewhere; they were contextualised, absorbed, and moved past.

This approach to accountability set an early pattern. Serious compliance failures resulted in leadership movement, not leadership consequence.

Point of Merger: Leadership Consolidation

Accord Housing Group entered the merger from a different position. Its long-standing chief executive, Dr Chris Handy, retired in March 2021 after more than 30 years in post. Under his leadership, Accord had become well known for its work in modular development and specialist housing delivery.

The merger between GreenSquare Group and Accord took effect on 1 April 2021, creating GreenSquareAccord, a 25,000-home housing and care association with a national footprint. Leadership of the merged organisation was not shared or transitional. Ruth Cooke, previously chief executive of GreenSquare, became chief executive of the new entity.

Publicly, the arrangement was described as a “merger of equals”. In practice, executive leadership continuity sat firmly with GreenSquare. The GreenSquare board structure became dominant, and strategic direction flowed from the GreenSquare side of the organisation. Accord’s chief executive had stepped aside, while GreenSquare’s leadership moved forward intact into the enlarged organisation.

The messaging around the merger was confident and ambitious. It promised scale, resilience, and increased capacity to invest in existing homes. It spoke of improved services, expanded care provision, modern methods of construction, and the delivery of up to 1,000 new homes a year. Sector bodies welcomed the deal and framed it as a positive step for growth and innovation.

What matters in hindsight is not the optimism of those statements, but the accountability that followed.

When safety failures, regulatory intervention, Housing Ombudsman investigation, and governance downgrades later emerged, there was no change at the top. Other senior roles have since turned over — including board appointments and the departure of the chief finance officer in late 2024 — but the chief executive role has remained unchanged throughout.

This continuity sharpens the central issue. GreenSquare entered the merger with known compliance failures, assumed leadership control of the merged organisation, and retained that control as problems multiplied. Responsibility cannot be displaced onto legacy structures or inherited stock. The outcomes of the merger sit squarely with the leadership that designed it, promoted it, and continues to lead it.

Promises Made Before the Merger

Before the merger was approved, residents were not asked to accept uncertainty or risk without reassurance. They were given clear, written assurances about leadership focus, regulatory learning, safety compliance, and the benefits the merger would deliver.

In August 2020, during the formal consultation on the proposed merger, Ruth Cooke wrote directly to residents to address concerns about repairs, regulatory intervention, and the organisation’s ambitions as a landlord. In that correspondence, she explicitly acknowledged the 2019 regulatory notice issued to GreenSquare and described 2018/19 as “a challenging year” for the organisation.

Crucially, she stated that lessons had been learned and that “substantial improvements” had already been made in response to the regulator’s recommendations. She linked these improvements to changes at executive and board level, including her own appointment, and said that from “day one” her absolute focus had been on meeting landlord health and safety obligations and ensuring that previous mistakes were not repeated.

The proposed merger with Accord was presented as a solution to historic weaknesses. Residents were told that a larger organisation would have more resources, increased capacity, and greater resilience. The merger was described as an opportunity to invest more in existing homes and neighbourhoods, expand locally focused services, and deliver improved outcomes for customers across a wider operating area.

The language used was unambiguous. The merger was framed as a “merger of equals” that would create a stronger organisation, better able to deliver the priorities of GreenSquare’s corporate plan and to become, in Cooke’s words, “a brilliant landlord”.

Financial reassurance featured heavily in this narrative. In the same correspondence, residents were told that GreenSquare was already financially strong. Cooke highlighted the harmonisation of terms with existing and new lenders, the agreement of new revolving credit facilities, and the consolidation of borrowing. This was presented as evidence that the organisation was in a “really healthy position” with increased capacity to manage the business more effectively and improve services.

In December 2020, following further engagement, Cooke again wrote to acknowledge that issues raised by residents should have been resolved far sooner and should not have required escalation. She apologised on behalf of the organisation and spoke about improving customer experience, strengthening feedback mechanisms, and developing better processes for repairs, service charges, and communication.

She also invited residents to take a more formal role in shaping services, including participation in a customer panel reporting directly to the board and involvement in future work on service charge setting and communication. The message was one of partnership, learning, and renewed focus on landlord performance.

These were not abstract aspirations or marketing slogans. They were specific assurances, given directly to residents, in advance of a major structural change. They acknowledged past failure, claimed improvement, and set clear expectations about safety, service delivery, and accountability.

What matters is not that these promises were made, but that they provide a benchmark against which everything that followed can and must be judged.

Leadership Change and Continuity

The period surrounding the merger was marked by leadership change — but not evenly, and not at the top.

At GreenSquare, the regulatory intervention of 2019 resulted in a change of chief executive, with Ruth Cooke appointed to replace Howard Toplis. That change was framed as a reset following compliance failures, and as the start of a renewed focus on landlord responsibilities, governance, and safety.

At Accord, leadership change took a different form. Its long-standing chief executive, Dr Chris Handy, retired in March 2021 after more than three decades in post. His departure was not connected to regulatory action or organisational failure. It was a planned retirement that coincided with the final stages of merger preparation.

This matters because it removes ambiguity about responsibility. The merged organisation did not begin with shared or rotating leadership. There was no transitional co-leadership period and no external reset at chief executive level. The leadership team that took GreenSquare into the merger carried forward into GreenSquareAccord intact, with expanded scale and reach.

Since the merger, there have been changes elsewhere. Board roles have turned over. Senior executives have departed. The chief finance officer announced their exit in late 2024. A new board chair was appointed in 2024. These changes demonstrate that movement and renewal have occurred within the organisation.

What has not changed is the chief executive role.

As service failures mounted, regulatory scrutiny intensified, and Ombudsman intervention escalated, leadership continuity at the top remained absolute. That continuity is not incidental. It frames how subsequent decisions were made, how challenges were handled, and how accountability has been distributed — or avoided — as problems multiplied.

The Merger Promise - Scale, Stock, and Stability

The GreenSquare–Accord merger was publicly framed as a strategic move designed to strengthen both organisations and improve outcomes for residents. Scale was presented as the solution. More homes would mean more capacity, more resilience, and more ability to invest.

When the merger took effect on 1 April 2021, the newly formed GreenSquareAccord became a 25,000-home housing and care provider with a geographical reach stretching from Newcastle upon Tyne to Wiltshire. The size of the organisation was repeatedly emphasised as a benefit in its own right, signalling stability to funders, partners, and the wider sector.

Leadership messaging at the time focused on financial strength and future-proofing. The merger was described as a “merger of equals” that would create a stronger and more resilient organisation, better able to deal with future challenges. It promised increased investment in existing homes, improved services for current residents, and the delivery of significant numbers of new affordable homes each year.

At the centre of this narrative was Ruth Cooke. Her senior career prior to becoming chief executive was rooted primarily in financial leadership roles, including serving as a finance director. That background shaped the rationale for the merger itself. The case for combining GreenSquare and Accord was framed overwhelmingly in financial terms: increased borrowing capacity, improved covenant headroom, and the ability to access capital on more favourable terms as a larger organisation with more stock.

Financial capacity sat at the heart of the promise. Residents and stakeholders were told that a bigger balance sheet would translate directly into better landlord performance. More borrowing power would enable greater investment in existing homes, safer properties, and improved services. Stability in finance was presented as a proxy for stability in delivery.

The merger was also presented as an opportunity to broaden the organisation’s offer. Alongside core housing management, GreenSquareAccord spoke of expanding care and support provision, investing in modern methods of construction, and increasing development activity, all while maintaining a renewed focus on being a high-performing landlord.

These claims were not peripheral. They were the justification for the merger itself. Residents, councils, and sector bodies were asked to accept organisational disruption on the basis that scale would unlock improvement and that stronger finances would underpin better service delivery.

What this narrative did not centre on was people.

Despite repeated sector-wide claims that residents are “at the heart of everything we do”, the merger logic prioritised financial engineering over lived experience. The emphasis was on assets, borrowing, and resilience, not on whether existing homes were safe, whether services were responsive, or whether residents felt heard. The same was true internally, where financial stability was elevated above the day-to-day realities faced by staff and residents alike.

Post-Merger - Safety First in Name Only

The gap between the merger’s promises and operational reality emerged quickly.

Within months of GreenSquareAccord coming into existence, the organisation was subject to regulatory action over failures to meet basic landlord safety obligations. In October 2021, the Regulator of Social Housing issued a regulatory notice after concluding that the landlord had failed to comply with statutory requirements relating to fire safety, electrical safety, and asbestos management.

These were not minor or technical shortcomings. The regulator identified failures in systems designed to ensure residents were safe in their homes, with the potential for serious detriment. The issues related to fundamental landlord duties — the very responsibilities that the merger had claimed scale and financial strength would improve.

The timing matters. This regulatory intervention occurred less than a year after the merger completed and after repeated assurances that lessons from previous compliance failures had been learned. It was not the discovery of historic issues buried deep in legacy systems. It was evidence that the merged organisation was not exercising effective control over safety-critical functions.

The response was procedural rather than transformational. Assurances were given, improvement plans referenced, and internal processes adjusted. What did not change was leadership, governance approach, or organisational posture. Safety failures were treated as matters to be managed and reported through regulatory channels, not as indicators of a deeper leadership or cultural problem.

For residents, the consequences were immediate and practical. Safety concerns remained unresolved, communication was slow or inconsistent, and confidence in the landlord’s ability to meet basic obligations was undermined. The promise that scale would deliver safer homes did not materialise when it mattered most.

The October 2021 regulatory notice established an early and critical pattern. Despite a merger explicitly justified on the basis of improved capacity, GreenSquareAccord was unable to demonstrate control over core safety functions. Financial resilience existed on paper; operational competence did not consistently follow.

This was not an isolated warning. It was the first clear indication that the merger had not delivered the step change in landlord performance that residents and stakeholders had been promised.

As safety and service failures persisted, residents escalated concerns through formal complaints processes. These escalations were not isolated or speculative; they reflected repeated attempts to resolve issues that had not been addressed through routine landlord responses.

By December 2023, those concerns had reached ministerial level. Following six findings of severe maladministration by the Housing Ombudsman and the launch of a special investigation into GreenSquareAccord, the Secretary of State for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities, Michael Gove, wrote directly to Ruth Cooke as chief executive.

The letter was explicit. It described the six findings of severe maladministration as “quite simply appalling” and stated plainly: “You have failed your residents.” It set out examples of prolonged inaction, including years-long failure to address pest infestation, excessive delays in responding to noise complaints from a vulnerable resident, and serious repair failures that left a resident with a faulty boiler and unresolved roof defects. In one case, more than 31 months had passed between an issue being reported and any meaningful intervention.

The Ombudsman’s findings, as summarised in the ministerial correspondence, identified common failures across the cases: excessive delays, poor communication, inadequate record-keeping, and failure to act in accordance with GreenSquareAccord’s own policies — particularly where residents were vulnerable. These were not borderline judgements. They were systemic failures.

The Secretary of State made clear that the decision to launch a special investigation reflected GreenSquareAccord’s repeated failure to take the necessary action expected of a social landlord. He confirmed that he would be taking a “personal interest” in the outcome of the investigation and that officials would arrange for GreenSquareAccord’s leadership to meet with ministers to discuss the findings.

In parallel correspondence, the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities acknowledged resident experiences and confirmed that ministers were meeting with GreenSquareAccord to hear how it intended to address concerns raised by residents and issues identified by the Housing Ombudsman. The department explicitly referenced the importance of tenant voice, regulatory enforcement, and the strengthened powers introduced under the Social Housing (Regulation) Act.

For residents, this escalation was not theoretical. It followed prolonged attempts to engage with GreenSquareAccord directly, attempts that were described as slow, combative, or ineffective. In some cases, efforts to mediate or seek resolution were met not with action, but with restrictions on communication and attempts to manage or contain scrutiny.

The Ombudsman’s intervention, reinforced by ministerial correspondence, marked a clear shift. What residents had been raising for years was now formally recognised as institutional failure. The problems were no longer framed as individual complaints, but as evidence of systemic breakdown in service delivery, complaints handling, and leadership oversight.

Systemic Failure Confirmed

The Housing Ombudsman’s special investigation report, published in October 2024, removed any remaining doubt that the issues at GreenSquareAccord were isolated or historical. The report identified clear indicators of systemic failure across the organisation.

The Ombudsman concluded that GreenSquareAccord had repeatedly failed to deliver effective services, failed to learn from previous complaints, and failed to put in place robust systems to prevent recurrence. The findings went beyond individual case handling and pointed directly to weaknesses in governance, oversight, and organisational culture.

Central to the report was the conclusion that complaints were not being treated as early warnings of failure. Instead, they were managed defensively, with delays, fragmented responses, and an absence of meaningful escalation. The Ombudsman found that lessons from upheld complaints were not consistently embedded across the organisation, resulting in the same types of failures recurring in different homes and regions.

The report also raised explicit concerns about whether the merger itself had contributed to declining service delivery. Rather than delivering the promised resilience and improvement, the integration of two organisations appeared to have weakened operational grip. Responsibilities were unclear, accountability was diluted, and residents were left navigating a system that struggled to respond coherently to even basic issues.

This mattered because the merger had been justified on the basis that scale would improve landlord performance. The special investigation reached the opposite conclusion: that the organisation had grown larger without strengthening its ability to manage risk, deliver services, or protect residents from harm.

Despite the seriousness of these findings, the response from leadership focused on assurances and process changes rather than accountability. Action plans were referenced, commitments were restated, and confidence was expressed that improvements were underway. What did not change was who remained responsible for the failures identified.

For residents, the significance of the special investigation was not symbolic. It validated experiences that had long been dismissed or minimised and confirmed that the problems they faced were structural, not personal. It also raised an unavoidable question: if an organisation can reach the point of ministerial intervention, severe maladministration findings, and a special investigation without leadership consequence, what threshold of failure actually exists?

The special investigation did not mark a turning point in accountability. It marked a confirmation of how far standards had fallen under a leadership structure that remained intact.

Regulation, Downgrades, and the Absence of Consequence

Alongside the Housing Ombudsman’s findings, regulatory and financial scrutiny of GreenSquareAccord intensified. The pattern that emerged was consistent: repeated identification of weakness, followed by mitigation and reassurance — but no leadership consequence.

In October 2025, the Regulator of Social Housing published an updated regulatory judgement on GreenSquareAccord. The organisation was graded C2 for consumer standards, meaning that weaknesses were identified and improvement was required. Its governance rating was downgraded to G2, signalling that governance arrangements needed to improve. Financial viability was retained at V2, indicating that while the organisation remained viable, its capacity to manage risk had weakened.

The regulator explicitly referenced ongoing pressures arising from increased investment requirements, including building safety and stock condition, which were reducing headroom and limiting flexibility. It also pointed back to the earlier regulatory notice issued in 2021, confirming that safety compliance failures remained relevant rather than resolved.

At the same time, financial markets were drawing similar conclusions. In February 2024, Moody’s Investors Service downgraded GreenSquareAccord’s credit rating from A3 to Baa1. The rationale was unambiguous. Moody’s cited tight covenant headroom, high levels of debt, and governance risk. While the outlook was described as stable, the downgrade reflected a reduced margin for error.

This was not an abstract technical adjustment. Covenant headroom and governance confidence are central to how housing associations are judged by lenders, boards, and regulators. A downgrade of this nature signals concern about how effectively an organisation is being managed at senior level.

Despite these warnings, the organisation continued to present itself as stable and in control. Financial restructuring, loan consolidation, and refinancing activity ensured that debt servicing continued and access to capital was maintained. From a lender’s perspective, the organisation remained functional.

The result was a familiar imbalance. Financial risk was managed tightly, while service failure, regulatory concern, and resident harm were absorbed elsewhere. Weaknesses were acknowledged, but responsibility was diffused. Oversight bodies intervened, but leadership continuity was preserved.

What is striking is not that GreenSquareAccord faced regulatory and financial challenge. Many housing associations do. What is striking is the absence of consequence at the top despite repeated external findings across multiple domains: safety, complaints handling, governance, and financial resilience.

The regulatory framework identified failure. Credit agencies adjusted risk assessments. Ministers intervened. Yet leadership remained unchanged. The system proved capable of flagging problems, but not of enforcing accountability.

The message this sends is clear. As long as debt is serviced, covenants are managed, and lenders remain confident, even sustained regulatory concern does not translate into leadership change. The costs of failure are carried by residents, staff, and communities — not by those responsible for strategic direction.

Finance Stabilised, Failure Normalised, Business as Usual

By late 2024, GreenSquareAccord’s financial position had stabilised on paper, even as regulatory concern and service failure persisted.

After posting significant deficits in the years immediately following the merger — including a £28.6m deficit in 2022/23 and a £19.3m deficit the year before — the organisation reported a surplus of £3.9m in 2023/24. This marked the first annual surplus since the merger of GreenSquare Group and Accord Housing in April 2021.

That surplus was not achieved through improved service delivery or a transformation in landlord performance. It was delivered through contraction.

As part of its “Simpler, Stronger, Better” strategy, GreenSquareAccord began selling off sections of its housing stock, particularly older homes assessed as expensive to maintain or upgrade. Properties were disposed of through sales and auctions, including in smaller communities and villages, reducing the availability of affordable social housing in those areas. Alongside this, offices were closed or consolidated, and the organisation reduced its physical footprint.

GreenSquareAccord framed these actions as prudent asset management across a 25,000-home portfolio, arguing that divestment from older stock was necessary to focus investment on core services and long-term viability. In practice, financial recovery was achieved by shrinking the organisation’s obligations rather than strengthening its capacity to deliver.

During the same period, residents and community groups raised concerns about the impact of these decisions. Reports pointed to pressure on repairs budgets, the loss of local presence, and reductions in care and support services. Financial performance improved, but the experience on the ground did not reflect a landlord becoming more responsive, safer, or more accountable.

Financial markets nevertheless responded to the stabilisation. Although Moody’s Investors Service had downgraded GreenSquareAccord in February 2024 — citing tight covenant headroom, high debt levels, and delivery risk associated with asset sales — the outlook remained stable. From a lender’s perspective, the organisation had regained control.

In October 2024, further evidence of this finance-first outcome emerged. Jo Makinson, GreenSquareAccord’s chief financial officer since January 2022, announced she would leave the organisation in December to take up a newly created chief investment officer role at Abri. Her departure followed the return to surplus and the successful execution of the financial recovery strategy.

The sequence is instructive. Deficits triggered urgent action. Assets were sold. Offices were closed. Debt was managed. A surplus was restored. Senior finance leadership moved on. What did not change was the lived experience of residents or the accountability of those at the top.

This is the point at which failure becomes normalised. Financial distress demands intervention; service failure does not. As long as lenders remain confident, covenants are met, and balance sheets improve, leadership remains protected. The organisation can contract, dispose, and retreat — and still be judged a success.

That is how failure stops sticking.

When Challenge Is Treated as Disruption

As financial pressure was brought under control, a different pattern became clearer: challenge was no longer treated as a warning signal, but as a risk to be managed.

Residents who continued to raise concerns about safety, service failure, or accountability increasingly encountered procedural barriers rather than resolution. Engagement shifted away from problem-solving and toward containment. This was most visible in the way sustained challenge was reframed as disruption.

In November 2021, GreenSquareAccord introduced formal restrictions on how I could communicate with the organisation. These restrictions were imposed following my attempts to escalate unresolved issues and to support other residents in doing the same. The organisation acknowledged service failures but stated that it needed to balance responding to me against “ensuring resources are appropriately deployed to servicing the needs of other customers”.

The effect was not balance; it was exclusion.

Communication was restricted to a single generic email address. Messages sent to named staff or senior figures would not be responded to. My involvement in supporting other residents was described as creating a “false process”, despite those residents exercising their own rights to raise complaints. The organisation also raised concerns about online content and public commentary, framing scrutiny itself as problematic.

This approach marked a shift in posture. Rather than treating persistent escalation as evidence that systems were failing, GreenSquareAccord treated the person escalating as the issue. Accountability was redirected away from organisational performance and toward individual behaviour.

The framing is important. At the same time that GreenSquareAccord publicly promoted strategies centred on customer voice, engagement, and improvement, it was privately restricting contact, narrowing channels of communication, and seeking to limit scrutiny. The message to residents was implicit but clear: challenge would be tolerated only within tightly controlled boundaries.

For those without the time, confidence, or resilience to persist, this approach was effective. Complaints stalled. Escalation became exhausting. Many residents simply disengaged. What remained visible to the organisation were not the full scale of unresolved issues, but the reduced number of people still willing to push.

This is how service failure becomes quieter rather than resolved. Problems do not disappear; they are displaced. Those who continue to raise them are managed, restricted, or labelled, while the organisation points to reduced noise as evidence of improvement.

In this context, financial recovery and reputational management became mutually reinforcing. As long as outward indicators were stabilised — surpluses restored, lenders reassured, strategies refreshed — internal challenge could be contained without consequence at leadership level.

The cost of that containment was borne elsewhere: by residents whose concerns went unanswered, by communities whose voices were sidelined, and by a system that mistook silence for success — and then promoted that silence as gospel, repeated ad nauseam until it became accepted truth.

A Restriction That Never Ended

The communication restrictions imposed on me in late 2021 were presented as proportionate, evidence-based, and subject to review. They were justified on the basis of alleged impact on staff time and organisational resources. No independent evidence was ever provided to substantiate those claims.

Despite subsequent findings of severe maladministration by the Housing Ombudsman, a ministerial rebuke, and formal regulatory concern, the restrictions remained in place. They were not lifted following the Ombudsman’s special investigation. They were not reconsidered after the organisation admitted statutory failings under Section 22 of the Landlord and Tenant Act 1985. They were not revisited after failed legal action and costs awarded against the landlord.

Instead, the restrictions hardened.

Contact continued to be funnelled through limited channels. Attempts to engage senior leadership were ignored or deflected. Legitimate scrutiny — including evidence-based commentary, documentation of outcomes, and support for other residents — was reframed as conduct requiring control rather than engagement.

This matters because the justification for the restrictions did not survive scrutiny. The organisation’s own failures were repeatedly confirmed by external bodies. The narrative that escalation was unreasonable or disproportionate collapsed under the weight of Ombudsman findings, regulatory notices, and ministerial correspondence. Yet the controls remained.

The purpose of the restriction therefore shifted. It was no longer about managing behaviour. It became about managing exposure.

By maintaining the contact management plan without evidential foundation, GreenSquareAccord insulated senior leadership from ongoing challenge. It limited the flow of uncomfortable information upward. It reduced reputational risk by narrowing who could speak, how, and to whom.

This approach sat in direct tension with public commitments to transparency, learning, and tenant voice. While strategies and reports emphasised engagement and improvement, the lived reality for those who challenged the organisation was restriction and silence.

Crucially, these decisions sat within the gift of the chief executive. The continuation of the restrictions was not an administrative oversight. It was a governance choice, exercised repeatedly and without external mandate.

The effect was predictable. Scrutiny diminished. Voices were marginalised. Accountability was deferred.

And once again, the pattern repeated: external bodies confirmed failure; internal controls suppressed challenge; leadership remained untouched.

Hype, Retreat, and the Cost of Failure

The closure of LoCaL Homes completes the post-merger pattern.

In January 2026, GreenSquareAccord confirmed that it would close its Walsall-based offsite manufacturing subsidiary, LoCaL Homes, after failing to secure a buyer. The factory had been put up for sale in September 2025. When no viable purchaser emerged, the business was shut down and 35 jobs were lost.

LoCaL Homes had been promoted as part of GreenSquareAccord’s forward-looking strategy — an emblem of innovation, modern methods of construction, and ambition to lead the sector. In practice, the business operated at a loss and became unsustainable. The decision to close it was framed as necessary, aligning with a stated intention to “simplify” and refocus on core landlord services.

The language is familiar. Financial pressures. Difficult decisions. Responsible stewardship.

What followed is also familiar. The consequences landed with staff and communities. The strategic retreat was executed quietly. Leadership continuity remained unchanged.

The timing is instructive. The closure followed shortly after GreenSquareAccord reported its first post-merger surplus of £3.9m. That surplus was achieved after exiting loss-making services, impairing assets, selling homes, consolidating offices, and narrowing the organisation’s scope. Financial recovery was secured by contraction. Strategic experimentation was abandoned. Jobs were lost.

At the same time, GreenSquareAccord continued to promote celebratory narratives elsewhere. For example, the organisation publicly highlighted a royal visit to a Gloucestershire domestic abuse support service, positioning itself within a positive, values-driven story of care and community impact. The service itself is not in question. What matters is the contrast.

As substantive areas of delivery — offsite manufacturing, care operations, local presence — were closed, sold, or exited, the organisation maintained a public emphasis on symbolic association and positive visibility. Celebration remained. Delivery was reduced.

This contrast runs through the post-merger period. When initiatives are launched, they are promoted as evidence of leadership and vision. When they struggle, they are reclassified as non-core. When they fail, they are closed. The organisational footprint shrinks. The leadership record does not.

LoCaL Homes was not a peripheral experiment. It was a strategic decision endorsed at executive level and used to signal ambition and sector leadership. Its failure adds to a growing list of outcomes that follow the same trajectory: promise, difficulty, retreat, and redistribution of cost away from those who made the decisions.

The pattern is now well established. Financial recovery is prioritised. Risk is contained. Exposure is managed. Staff, residents, and communities absorb the impact. Leadership remains intact.

This is how failure is not just tolerated, but normalised — and why it never reaches the top.

Failure, Accepted and Funded

Taken together, the record is no longer ambiguous.

GreenSquareAccord’s post-merger history shows repeated safety failures, severe maladministration, regulatory downgrade, ministerial intervention, financial distress followed by recovery through contraction, suppression of challenge, staff layoffs, and the collapse of a flagship strategic venture. None of this is disputed. It is documented by regulators, the Housing Ombudsman, ministers, credit agencies, and the organisation’s own statements.

What is more striking than the failures themselves is how widely they have been accepted.

Despite this record, Ruth Cooke continues to be treated as a credible sector leader. She sits on the board of the National Housing Federation, a position that confers legitimacy, influence, and protection. It signals to government, councils, and funders that this is leadership to be trusted, irrespective of outcomes experienced by residents.

Around that acceptance sits a wider ecosystem of silence. Third-party suppliers, consultants, and contractors are reluctant to step into the conversation. Not because the issues are unclear, but because they are commercially inconvenient. GreenSquareAccord controls significant budgets. There is money to be made, and few are willing to jeopardise access to it by asking uncomfortable questions. Compliance is rewarded. Challenge is avoided.

All of this is framed beneath the language of “not-for-profit”. Yet the reality is more complex. While services fail, staff are laid off, homes are sold, and residents struggle to be heard, senior executives continue to be paid well. Salaries, bonuses, and career progression remain insulated from outcomes. Risk is pushed downward. Reward stays at the top.

This leads to the question the sector continues to avoid.

How long until Ruth Cooke is given the same soft landing afforded to others before her — like Howard Toplis — a quiet exit, a respectable new role elsewhere in the sector, and a financial settlement that carries her comfortably into retirement?

And if that happens, who compensates the residents? Who takes responsibility for making homes safe? When are the promises made to residents finally realised — or will they, too, be quietly closed down and wrapped in polished narrative control by an organisation that clearly knows how to play the game, just not to the benefit of its residents or the communities it is paid to support and serve?

At what point does accountability reach the top?

Local authorities continue to transfer millions of pounds of Housing Benefit to GreenSquareAccord every year. This is public money, paid not as an act of faith, but on the assumption of competence, transparency, and lawful stewardship.

The unresolved question is no longer whether this leadership has failed. The documented record answers that beyond doubt.

The real question is why councils, regulators, and the wider housing sector continue to endorse, enable, and fund that failure — and why public money is still being handed over without meaningful scrutiny or consequence.

GreenSquareAccord was given the right of reply, as it always is. As always, they did not respond. When faced with documented facts and legitimate questions, silence is the default. This has become the GreenSquareAccord way.

Sources and references

Regulator of Social Housing

Regulatory Notice: GreenSquare Group (March 2019)

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/regulatory-notice-greensquare-groupRegulator of Social Housing

Regulatory Notice: GreenSquareAccord (October 2021)

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/regulatory-notice-greensquareaccordRegulator of Social Housing

Regulatory Judgement: GreenSquareAccord (October 2025)

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/greensquareaccord-regulatory-judgementHousing Ombudsman Service

Severe maladministration findings against GreenSquareAccord

https://www.housing-ombudsman.org.uk/landlord/greensquareaccord/Housing Ombudsman Service

Special Investigation Report: GreenSquareAccord (October 2024)

https://www.housing-ombudsman.org.uk/special-investigation-into-greensquareaccord/Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities

Secretary of State correspondence following Ombudsman findings (December 2023)

https://questions-statements.parliament.uk/written-statements/detail/2023-12-07/hcws109Inside Housing

GreenSquare replaces chief executive after regulatory breach (2019)

https://www.insidehousing.co.uk/news/greensquare-replaces-chief-executive-after-regulatory-breach-60606Inside Housing

Howard Toplis appointed chief executive of Tai Calon (April 2020)

https://www.insidehousing.co.uk/news/howard-toplis-appointed-chief-executive-of-tai-calon-65834Inside Housing

GreenSquareAccord posts first surplus since merger (2024)

https://www.insidehousing.co.uk/news/greensquareaccord-posts-first-surplus-since-merger-86869Inside Housing

GreenSquareAccord CFO Jo Makinson to join Abri (October 2024)

https://www.insidehousing.co.uk/news/greensquareaccord-cfo-set-to-join-abri-88437Moody’s Investors Service

GreenSquareAccord credit rating downgrade (February 2024)

https://ratings.moodys.com/credit-ratings/GreenSquareAccord-credit-rating-100040043GreenSquareAccord

Merger consultation correspondence to residents (2020)

https://www.greensquareaccord.co.uk/about-us/greensquareaccord-merger/GreenSquareAccord

Annual accounts and financial statements

https://www.greensquareaccord.co.uk/about-us/our-financial-performance/GreenSquareAccord

LoCaL Homes closure announcement (January 2026)

https://www.greensquareaccord.co.uk/news/finance/local-homes-closure/